Roots : “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” - Part II

Norms

The central norms of American foreign policy—self-government, sovereignty and national identity, collective self-defense, rule of law— became so generally accepted over time that few individuals paused long enough to reflect upon the depth of their commitments. The extent that Americans came to regard their political values as articles of faith was caught over fifty years ago by Louis Hartz, who saw this faith so deeply rooted and widely accepted that it had become “one of the most powerful absolutisms in the world.” So secure were Americans in their messianic belief system, Hartz wrote, that,

"its very intensity betrayed an inescapable element of doubt. But the American absolutism, flowing from an honest experience with universality, lacked even the passion that doubt might give. It was so sure of itself that it hardly needed to become articulate, so secure that it could actually support a pragmatism which seemed on the surface to belie it."8

In support of Americanism as it developed over time, including racial stereotypes, hubris lodged within the exceptionalist idea and messianic crusades, Professor Michael H. Hunt has labeled the American doctrine an “ideology” based upon political culture. As an absolutist set of belief systems he sees, as did Louis Hartz, the absolutism of America’s foreign affairs worldview:

“The corollary, and in large measure the consequence, of this continuity in American foreign policy ideology is the absence of a self-consciousness about that ideology. Because of a remarkable cultural stability, Americans have felt no urgent need to take their foreign policy ideology out for major overhaul or re- placement but have instead enjoyed the luxury of being able by and large to take it for granted.”9

Whether used as an authentic ideology or not, the utility of a unique and powerful view of themselves and the world has served as an integrating system throughout American history. As a mainstay of the polity, the political, moral, and legal tenets of the American belief system in world politics served as a powerful force to integrate and solidify both individuals and society to bestow collective action with purpose and meaning.

Through two centuries of foreign relations, these underlying principles gave life and direction to U.S. foreign policy during periods of both calm and crisis. At times, they may have served as little more than window dressing; at other times they may have served as guides to action. In either case, in the background or the foreground, American principles were real and present, weaving like a thread through the long history of actions and explanations of U.S. foreign relations.

Many of these beliefs appeared in statements of purpose and doctrine, including the Declaration of Independence, the Federalist Papers, the Monroe Doctrine, the Open Door policy toward China, U.S. military interventions in Latin America and elsewhere, in Woodrow Wilson’s crusade during World War I. They appeared prominently in the many years of political and moral appeals made to the public through the trials of World War II and the Cold War. George W. Bush vigorously applied them after 9/11, though whether with judgment or wisdom is still hotly debated.

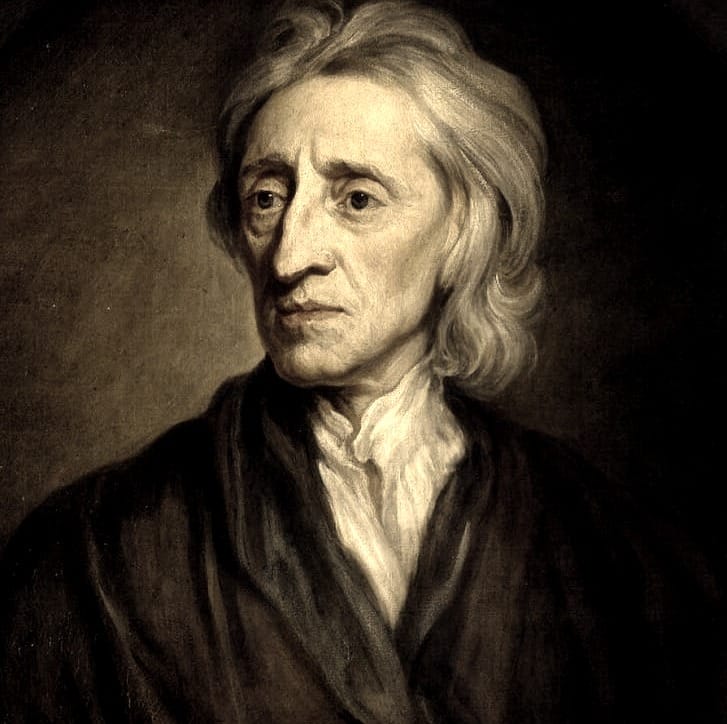

The fact that the American principles have served to integrate the complexities of foreign policy and to transform them into broadly accepted and easily understood assertions has given them a unique value to the public and has provided them with a certain life of their own. Such norms reflect over three hundred years of tradition and, to a significant degree, are rooted within the values of classical “Lockean liberalism.” Throughout the vast majority of its history, either implicitly or explicitly, American foreign relations were guided by a set of underlying principles rooted in the colonial experience and the political writings of the English philosopher, John Locke.

The American commitment to Locke in foreign policy design has been so strong that by one account we “have embraced him wholeheartedly and have traditionally endowed his philosophy with a sanctity that our individualism belies. ... Locke’s influence has run rampant ever since the American colonies began to ponder on the nature of their experience in the New World.”10

Locke wrote one hundred years before the American Revolution and his influence was more important in the colonies than in England. Locke’s great theme was freedom and his greatest contribution was that without law there can be no freedom. He has been called America’s philosopher king and is the principle reason that this country has always been “a nation of laws, not men.” But self-preservation, he wrote, is the most powerful force in human nature, for without that quality that there can be no political legitimacy, no laws and, at bottom, no social order. Properly led, self-preservation provides both safety and plenty. Ignored, or dismissed, it will provide anarchy and violence and a wholesale destruction of life and property.

The attraction of early American society to his teachings was derived from his principles regarding the sanctity of property and the right of self-defense. “Every man has a property in his own person,” a core belief of classical liberalism, was also the central belief of John Locke. The corollary to this was Locke’s emphasis that “nobody has any right [to this property] but himself.” Society exists in order to protect and to increase one’s property through “an original compact between property owning individuals and government that must therefore serve the needs and purposes of the governed.”11

Since one’s person is also one’s property, it is in accord with natural law to protect and extend this property. Since the original compact between government and the governed exists it is equally natural that government protect property and its accumulation. All attempts to encroach upon property and national territory by force, furthermore, are contrary to natural law and the idea of self-government. Thus, Locke extends his beliefs into an integrated philosophy of individual rights and property, government by the consent of the governed, rule of law, and self-defense through collective action—all central ingredients of the American belief system, and by extension, to its foreign affairs.

Locke’s economic writings gave to his readers, especially in the American colonies, a profound sense of the spirit of enterprise and freedom of independent action long before Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. The objections against the rise of capitalism have always centered around the allegations of inequality and injustice between classes, those who own and those who do not. Locke’s solution, which was a powerful component of the American dream, was simple: increase. In Locke’s words, again:

"He who appropriates land to himself by his labor does not lessen but increase the common stock of mankind. For the provisions serving to the support of human life produced by one acre of enclosed and cultivated land are … ten times more than those which are yielded by an acre of land of an equal richness lying waste in common. And therefore he that encloses land, and has a greater plenty of the conveniences of life from ten acres than he could have from a hundred left to nature, may truly be said to give ninety acres to mankind."11

The notion that men combine to form autonomous societies through the consent of the governed led to Locke’s formulations regarding collective identity—the commonwealth. Men who live in a single community form natural ties since their property rights are linked together. Such a commonwealth forms a single body and “... their first care and thought cannot but be supposed to be how to secure themselves against foreign force.”12

Although Locke is most famous for his dictum on the nature of domestic order (the best government is that which “governs least”) his doctrines relating the role of self-defense based upon property, self-rule, national identity and the natural rights of man are equally profound. The First Principles of order, he maintained, came from the need for defense and survival. He emphasized that “an injury done to a member of their body engages the whole in the reparation of it,” and that the first task of government is “the preservation of the society.”13

Locke went even further and elevated the task of self-defense to a higher moral plane, a “fundamental, sacred and unalterable law of self- preservation.” This link between morality and warfare culminated in a just war theory of Lockean thought which justified war beyond self-defense to a natural right to fight an anticipated attack. Locke wrote that it was

“lawful for a man to kill a thief who has not in the least hurt him, nor declared any design on his life ... because using force, where he has no right, to get me into his power, let his pretense be what it will, I have no reason to suppose that he who would take away my liberty would not, when he had me in his power, take away everything else.”14

In this sense, Locke is the natural father of the doctrine of pre-emptive war, a doctrine enshrined in U.S. foreign relations centuries before George W. Bush restored its mandate.

Locke also was an original spokesman for the universalistic strain of America’s foreign outlook by insisting upon a very close connection between self-preservation and the obligation to preserve the rest of mankind. Locke authority Robert Goldwin has identified this aspect of his philosophy in association with the need for a fierce vigilance:

“In example after example the execution of the duty to preserve others is coupled with the right to kill another man who threatens or might threaten one’s own preservation. The aggressor against me is to be treated as one unfit to associate with human beings, as a savage beast, and as therefore, a threat to all mankind.”15

Locke’s own words highlight the theory behind the famous early American flag displaying a coiled snake and the inscription, Don’t Tread On Me. It is, he wrote,

“reasonable and just I should have a right to destroy that which threatens me with destruction; for, by the fundamental law of nature, man being to be preserved as much as possible, when all cannot be preserved, the safety of the innocent is to be preferred; and one may make war upon him, or has discovered an enmity to his being, for the same reason that he may kill a wolf or a lion.”16

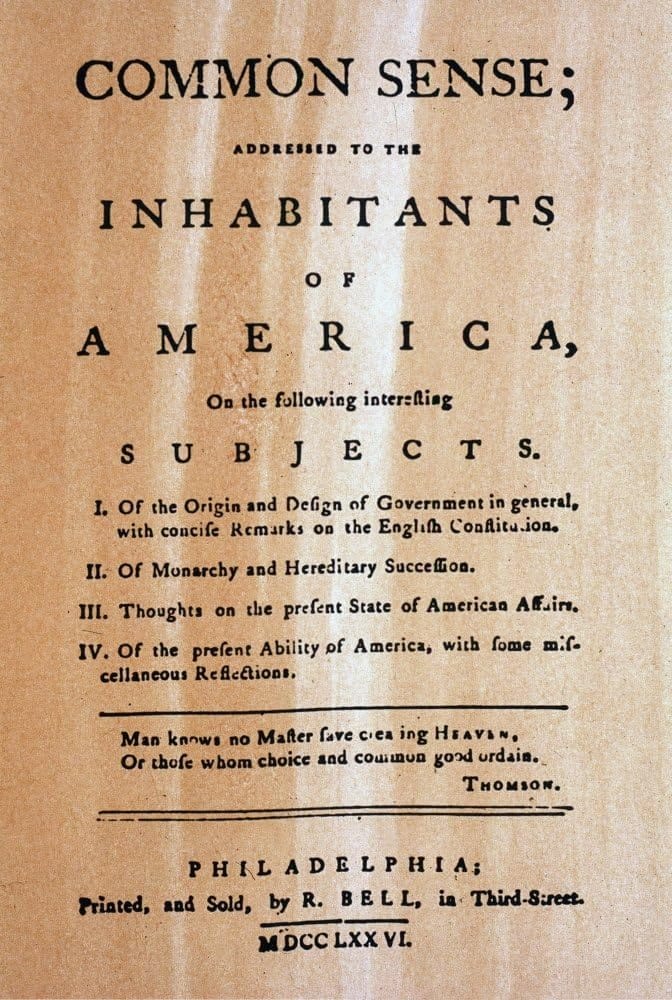

Locke’s arguments regarding the consent of the governed, the rights of property accumulation, self-government, and self-defense were integrated deeply within the mindset of colonial America as the New World thesis took hold. The principles of Locke’s political philosophy were given their first, and most doctrinaire, interpretation by Thomas Paine in Common Sense (1776), the original explanation of the dynamics of the American principles of foreign policy. The moralities of property, self-government, and self-defense were transformed into a patriotic mission as American settlers developed a continental, and distinct, identity. Common Sense made Locke an American partisan and began a revolution:

“America is only a secondary object in the system of British politics. England consults the good of this country no further than it answers her own purpose. Wherefore, her own interest leads her to suppress the growth of ours in every case which doth not promote her advantage, or in the least interferes with it.”

Paine argued that only an independent, continental government, severed from England, could protect American life and values:

“We have boasted the protection of Great Britain, without considering that her motive was interest, not attachment; and that she did not protect us from our enemies on our account; but from her enemies on her own account, from those who had no quarrel with us or any other account, and who will always be our enemies on the same account.”17

Paine’s rhetoric provided public and political momentum in the colonies to the Lockean notion of the collective right to self-defense and the doctrine of sovereignty vested in the consent of the governed. The Declaration of Independence, written largely by Thomas Jefferson, a Locke disciple, espoused the great principles of revolutionary Lockeans, which subsequently became the American gospel of foreign policy:

• Self-defense: “as free and independent states [the colonies] have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce and to do all other acts and things, which independent men of right do;”

• Self-identity: [the revolutionists] were “mutually pledged to each other, [their] lives, fortunes and sacred honor.”

The influence of Locke’s Second Treatise on Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence has been so profound as to provoke scholars such as Carl Becker to write that “Jefferson copied Locke.”18 Louis Hartz went further in writing that “Locke dominates American political thought as no thinker anywhere dominates the political thought of a nation.”19

As examined by Professor Garrett Sheldon, the influence of Locke on the American political character, in the tradition of the Enlightenment and the colonial experience, traces the philosophy of John Locke in perfect sequence. Locke’s three theoretical categories, the nature of man, the nature of government, and the right of revolution, are pursued in the Declaration of Independence in precisely that order. Sheldon has demonstrated, word by word, how the Declaration is an altered version of Locke’s original thesis as developed in the Second Treatise. While revisionist scholars, such as J.G.A. Pocock, see both Republican and Aristotelian origins in the American Founding, this view is not necessarily inconsistent with the powerful influence of John Locke. As Sheldon has summarized it,

“The seemingly contradictory position of adhering to both ancient and modern conceptions is reconciled by Jefferson’s adaptation of Lockean freedom to serve the ends of classical freedom embodied in local democratic legislatures, and his belief that participatory republics would protect individual natural rights.”20

Aside from the theoretical splitting of hairs, the political foundations of revolution came from John Locke but it was Paine, Jefferson, and the generation of 1776 who did what he could not possibly have done: develop the philosophy of liberty and give it political power and national mission. The same generation, having consolidated the Revolution into the new nation, would provide guiding principles of foreign policy which reflected John Locke and the revolutionary origins of the American Republic.

In fact it was John Adams, years before the Revolution began, who gave birth to what was to become the unique American mission in foreign policy. In 1765 Adams delivered remarks that fairly represent the historical significance that the Founding Fathers attached to the American experiment with republican government. “I always consider the settlement of America with reverence,” he said, “as the opening of a grand scheme and design in Providence for the illumination of the ignorant, and the emancipation of the slavish part of mankind all over the earth.”21

Adams was even more exuberant after the Boston tea Party of December 1773, when colonists disguised as Indians dumped British tea crates into Boston harbor. “This is the most magnificent movement of all, “he wrote in his diary,

“There is a dignity, a majesty, a sublimity, in this last effort of the patriots that I greatly admire. The people should never arise without doing something to be remembered something notable and striking. This destruction of the tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have [sic, be] so important, and so lasting, that I can’t but consider it as an epoch of history.”22

Adams was not alone in his view that the birth of the American nation, with its embodiment of social and civic virtues, had a transcendent significance for the political transformation of mankind. Americans were often defined as a chosen people, as Pastor Ezra Stiles offered in 1783, where “The Lord shall have made his American Israel high above all nations which he hath made.”23 Thomas Paine’s fiery rhetoric offered American colonists a mission of historic significance, surpassing all previous endeavors of mankind. “We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” he wrote, “a situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand.”24

Washington himself was imbued with the notion of America the liberator, as when he once noted that “it will be worthy of a free, enlightened, and, at no distant period, a great nation, to give to mankind the magnanimous and too novel example of a People always guided by an exalted justice and benevolence.”25 In 1779 Washington reinforced morale by reminding Americans that “our cause is noble, it is the cause of mankind.”26

The United States was frequently likened to the ancient Roman Republic. Adams used the analogy often and the writings and speeches of Jefferson, Franklin, Hamilton, Jay, and others are dotted with allusions to Cicero, Cato, and Virgil. George Washington was compared to Cincinnatus and the U.S. Senate to that of Rome.

The revolution against England was more than a tax revolt; it had a deep moral and spiritual base. Thus, we find Benjamin Franklin, identified by some as a political realist, remarking during the Revolutionary War that the American cause is “the cause of all Mankind ... assigned us by Providence.”27 Thomas Paine was even more explicit, calling it “the most virtuous and illustrious revolution that ever graced the history of mankind.” Paine foresaw an eighteenth century new world order, with the United States able “to begin the world over again ... [as] the Mother Church of Government.”28

But Thomas Jefferson was perhaps the most expansive proponent of the worldwide importance of the American Revolution. “While we are securing the rights of ourselves and our posterity,” he wrote in 1790, “we are pointing the way to struggling nations who wish, like us, to emerge from their tyrannies also.”29 In the last days of his presidency Jefferson delivered an address which has striking parallels to the eloquence of John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address more than a century and a half later. In this speech to the citizens of Washington, Jefferson said:

“The station which we occupy among the nations of the earth is honorable, but awful. Trusted with the destinies of this solitary republic of the world, the only movement of human rights, and the sole depository of the sacred fire of freedom and self-government, from hence it is to be lighted up in other regions of the earth, if other regions of the earth shall ever become susceptible of its benign influence. All mankind ought then, with us, to rejoice in its prosperous, and sympathize in its adverse fortunes, as involving everything dear to man.”30

Many years later, in an 1821 letter to John Adams, Jefferson reiterated this faith in the power of American ideals:

“And even should the cloud of barbarism and despotism again obscure the science and liberties of Europe, this country remains to preserve and restore light and liberty to them. In short, the flames kindled on the fourth of July, 1776, have spread over too much of the globe to be extinguished by the feeble engines of despotism; on the contrary, they will consume these engines and all who work them.”31

Not even Jefferson could have appreciated the subsequent impact of such a forecast.

Even Alexander Hamilton, among the Framers closest to the European tradition of realpolitik, expressed his own belief that the American cause was also “the cause of virtue and mankind.” “The world has its eye upon America,” he wrote in 1784, “the cause of liberty has occasioned a kind of revolution in human sentiment. The influence of our example has penetrated the gloomy regions of despotism, and has pointed the way to inquiries which may shake it to its deepest foundations.”32

These were not just the fleeting sentiments of men flush with victory over the world’s then-ranking superpower, they were the deepest thoughts of perhaps the most profound and reflective group of thinkers ever assembled in one place at one time. This was, moreover, the consensus among the whole body of Founding Fathers during the critical early years of the United States, the seedtime of the Republic.

Thus, the crusading spirit of some of the more prominent twentieth century presidents—Wilson’s call to “make the world safe for democracy,” FDR’s “four freedoms,” Truman’s support for “free peoples,” Eisenhower’s declaration that “freedom is pitted against slavery,” Kennedy’s “summons ... to assure the survival and success of liberty” and Reagan’s challenge to the “evil empire”—appear to have deep roots in the original American political culture.

Thus, the origins of American nationalism and patriotism, and the rise of a political system based upon liberty, gave rise to the companion mission of the United States in world affairs. This mission was based on the distinctive quality of the social order established in the New World and by a conviction that this order, and the military victory over Great Britain, would ultimately make a significant contribution to the lasting freedom of mankind.

This mission has been prominent throughout the history of the United States, as politicians and statesmen with such divergent outlooks as Alexander Hamilton and Woodrow Wilson have articulated the idea that the American system of political democracy would become the model for the world. As the country matured and accrued world-class status this belief grew into a conviction that American power would ultimately provide for the distribution of liberty and democracy on a universal scale; what Jefferson once called an “empire for liberty.” From one century to the next, this outlook grew from a defensive shield to an offensive sword.

Thus, the crusading spirit of some of the more prominent twentieth century presidents—Wilson’s call to “make the world safe for democracy,” FDR’s “four freedoms,” Truman’s support for “free peoples,” Eisenhower’s declaration that “freedom is pitted against slavery,” Kennedy’s “summons ... to assure the survival and success of liberty” and Reagan’s challenge to the “evil empire”—appear to have deep roots in the original American political culture.

This belief system is uniquely American and has no counterpart anywhere on earth—with none on the horizon. It is, moreover, a belief system handed down through generations as an unquestioned faith in the righteousness of the American Way. Other countries have had their so-called day in the sun: England, France, Germany, Spain, Russia, Japan, Italy, but the sun has long set on all of their ambitions or pretensions. But the American cause still glows, as a cause removed from personality, and who is to say that it is not only in its infancy?

The wellspring of the original American worldview, Lockean liberalism, is also partially derived from the general spirit of the Enlightenment, with its emphasis on the need to discover the eternal laws which govern politics and its paradoxical stress on reason for the resolution of political conflict. Thus, the origins of American thought on international politics is liberal from history’s long perspective, reflecting the absence in colonial America of the feudal, clerical, and monarchical oppressions of the Old World Order.

The experience as an English colony also provided early Americans a vantage point in the evolution of democracy in the Mother Country. The channels of communication between England and America were always open and the colonists were able to note the gradual democratization taking place in England. This included the parallel growth of the importance of public opinion and popular support for decisions, especially the use of pamphlets, newspapers and tracts. Colonial Americans, to Britain’s dismay, were excellent students.

The colonies were also able to experience relationships with other countries, particularly France and the Netherlands, plus other colonies like themselves. From this experience grew patterns of thought regarding the importance of commerce in the world, awareness of the relevance of Europe’s constantly changing balance of power and the growing development of such lasting American principles as freedom of the seas, the rule of law, non-intervention, self-government, self-defense, and democracy versus monarchy.

The sum total of the early American experience with the outer world, and the critical departure point for the American belief system in foreign affairs, is the conscious and deliberately conceived idea of two separate “worlds.” The first, the “old” world, was identified as dominated by the dictatorship of the kings and courts of European rulers, which subordinated liberty and individual rights to the throne and conducted foreign affairs by power and expediency. The second, the “new” world, was seen as inspired by the unique growth of democratic government in colonial America, was dedicated to the fulfillment of the individual and personal liberty and the general observance of morality, law, and political principle in external relations. Between these divides there was no compromise.

As the colonists—and the later revolutionaries—saw it, the American role in the world was not essentially political, it was essentially a moral role and Americans were creators in a great moral experiment which produced a whole new kind of political community. The historian Cushing Strout reflected on the essence of this shared perspective as the United States embarked on its original mission:

“America is the land of the Future, where innocent men belong to a society of virtuous simplicity, enjoying liberty, equality and happiness; Europe is the bankrupt Past, where fallen men wander without hope in a dark labyrinth, degraded by tyranny, injustice and vice.”33

Notes

8. Hunt, Michael. Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), p. 13.

9. Weisband, Edward. The Ideology of Amercan Foreign Policy: A Paradigm of Lockian Liberalism. (Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE, 1973), p. 11.

10. Ibid. p. 12.

11. Locke, John. Two Treatises on Government. (London: printed for R. Butler, Bruton- Street, Berkeley-Square, 1821).

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid. 314-315; p. 302.

14. Ibid. p. 201-202.

15. Quoted in J. Michael Martinez. The Leviathan’s Choice. (Lantham, MD: Rowman & Littleman Publishers, Inc., 2002), p. 44.

16. Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government and a Letter Concerning Toleration. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), p. 107.

17. Paine, Thomas. Common Sense. (Philadelphia: Bartleby, 1999).

18. Becker, Carl. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co,1922).

19. Hartz, Louis. The Liberal Tradition in America. (United States: Harvest Books,1955), p.140.

20. Sheldon, Garret.The Political Philosophy of Thomas Jefferson. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991) p. 141-142.

21. Adams,John. Dissertation and the Cannon and Feudal Law. (Boston: Boston Gazette, 1975).

22. Adams, John. Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, Volumes 1-4: Diary (1755-1804) and Autobiography (through 1780). (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1961).

23. Stiles, Ezra. The United States Elevated to glory and Honor- A Sermon. (Hartford: 1783)

24. Paine, Thomas. Common Sense. (Philadelphia: Bartleby, 1999).

25. George Washington’s farewell address, 19 September 1796. http://gwpapers. virginia.edu/documents/farewell/transcript.html

26. Washington, George. A Collection. compiled and edited by W.B. Allen (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1988).

27. Paine, Thomas. Collected Writings. (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1955), p. 169;

28. Paine, Thomas. The Theological Works. (Boston: J. P. Mendum, 1859), p. 42

29. Jefferson, Thomas. The Works of Thomas Jefferson in Twelve Volumes. Federal Edition. Collected and Edited by Paul Leicester Ford.1904. (Thomas Jefferson to William Hunter, March 11, 1790)

30. Quoted in Washington, H. A., ed. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. Vol. VIII. (Washington, DC: Taylor & Maury, 1854), p. 158.

31. Quoted in Holmes, Jerry. Thomas Jefferson: A Chronology of His Thoughts. (New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2002), p. 288.

32. Hamilton, Alexander. The Works of Alexander Hamilton. (New York: J. F. Trow, 1851), p. 329.

33. Strout, Cushing. The American Image of the OldWorld. (NewYork: Harper & Row 1963), p. 19.