Roots : “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” - Part I

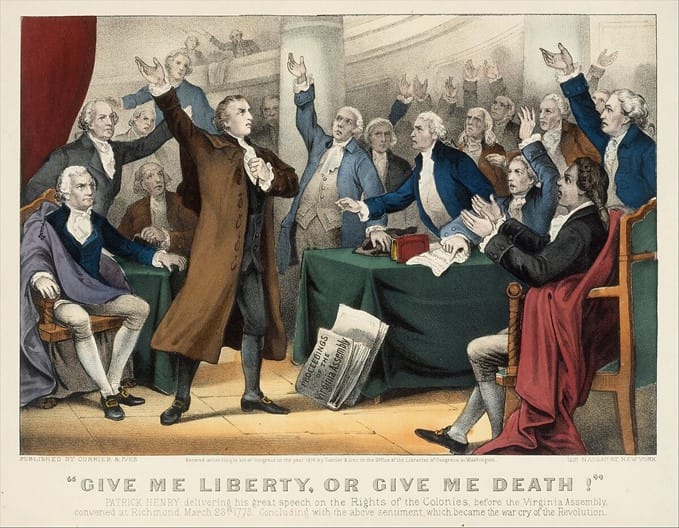

“Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death.” –Patrick Henry, 1775

Fires

President Biden’s Inaugural Address (2021) on behalf of national unity came as a welcome relief to a nation enveloped by divisions. The heart of Biden’s message was unity over division, as follows:

“Today, on this January day, my whole soul is in this: Bringing America together. Uniting our people. And uniting our nation. I ask every American to join me in this cause. Uniting to fight the common foes we face: Anger, resentment, hatred. Extremism, lawlessness, violence. Disease, joblessness, hopelessness. With unity we can do great things. Important things. We can right wrongs. We can put people to work in good jobs. We can teach our children in safe schools. We can overcome this deadly virus.”

While the kind of soaring rhetoric that the President employed, by definition, cannot be expected to guide daily policy, such inflated oratory has served since the beginnings of the Republic to define the general character of the American approach to the rest of the world. In this important respect, the address was not historic at all, but characteristic.

When President John Kennedy delivered a similar Inaugural Address in 1961, his words were welcomed almost universally. A new energy had been summoned, or so it seemed: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” Similar to Biden’s message on domestic issues, Kennedy electrified Americans to sacrifice on behalf of the cause of liberty around the globe: “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

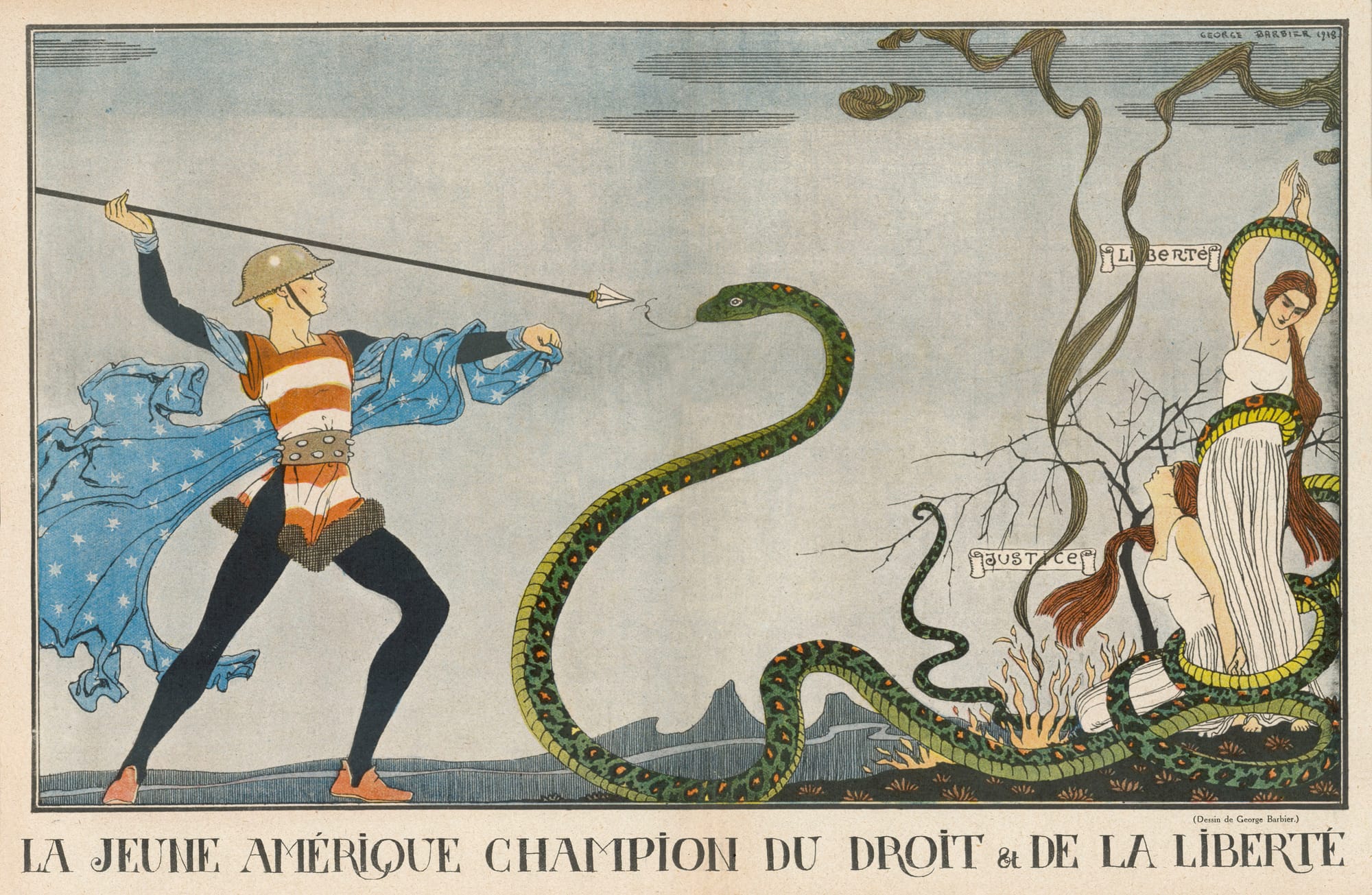

Kennedy’s theme was not original either but, in the context of the moment, it gave renewed credence to the doctrinal belief which has always provided the essential raison d’etre for the American role in the world. Such rhetoric has often been equated with Woodrow Wilson and his lofty pronouncements against tyranny and for freedom. A classic case was Wilson’s declaration of war message against Imperial Germany on April 2, 1917. Drawing upon foundations going back before 1776, Wilson emphasized the unique American call-to-arms because:

“right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts, - for democracy, for the rights of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations.”

Wilson was speaking from a deep heritage, in which even the trope matched over a period of centuries. The “fire” of liberty provided a strong and consistent metaphor, and it, too, began at the beginning. In the nation’s first Inaugural Address, April 30, 1789, George Washington told the country that the American democratic experiment represented “the sacred fire of liberty.” Thomas Jefferson spoke of America as “the sole depository of the sacred fire of freedom and self-government, from hence it is to be lighted up in other regions of the earth.”1

A century and a half later, JFK invoked a near-identical reference by proclaiming that, “The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it—and the glow from that fire can truly light the world.” Coming full circle, George W. Bush brought the past alive with his own version of the fire of liberty: “By our efforts, we have lit a fire as well—a fire in the minds of men. It warms those who feel its power, it burns those who fight its progress, and one day this untamed fire of freedom will reach the darkest corners of our world.” President Obama reminded the nation that the ideals of the Founding Fathers “still light the world, and we will not give them up for expedience’ sake.”

In other ways, both Bush and Obama echoed what Kennedy and others have pronounced as the American gospel. While rhetoric is not policy, it still reflects values and political direction. In America it has been quite consistent. Both noted that arms were necessary but insufficient. Kennedy reminded his generation that, “Now the trumpet summons us again—not as a call to bear arms … but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle.” Bush noted how the goal of world democracy is “not primarily the task of arms,” while similarly repeating his message that the struggle was open-ended and generational: “The great objective of ending tyranny is the concentrated work of generations.” Obama’s Inaugural Address noted this message by invoking history: “Recall that earlier generations faced down fascism and communism not just with missiles and tanks but with sturdy alliances and enduring convictions.”

Many Inaugurals brought forth the Creator, another theme rooted in the American political culture. Washington spoke of the American Republic as derived from that “which heaven itself has ordained.” Kennedy noted how the “rights of man come not from the generosity of the state, but from the hand of God.” George W. Bush mentioned God or God’s work on no fewer than six occasions, while Obama declared that “God calls on us to shape an uncertain destiny.”2

That is the purpose of rhetoric, a design for the practical aspect of statesmanship toward horizons not yet attained. This is essential for an ordered world.

In a larger dimension, such rhetorical consistencies reflect the political personality of the American culture and rise higher than the speech writers of any given generation. These are essentially intangible elements of the intellect and instinct, the so-called soft elements of national power. They include will, rhetoric, maturity, leadership, prudence, character, and vision. While such qualities embedded in the statements of American political leaders may have served as only theoretical guides, they nonetheless represent efforts toward future and better worlds. That is the purpose of rhetoric, a design for the practical aspect of statesmanship toward horizons not yet attained. This is essential for an ordered world.

The late Robert Strausz-Hupe, Professor Emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania and five-time U.S. Ambassador, summarized these qualities in his conclusion to Democracy and Foreign Policy. “No one should expect [others] to tell us where we are going – or where we ought to go,” he wrote. “That is the job of the statesman: foresight is the mark of his calling. His is the task to persuade the people to ‘silence their immediate needs with a view of the future.’ The history of democratic foreign policy is the history of men who succeeded or failed at this task.”3

Such foresight thus remains embedded within the character of the American nation, and it is within this character that a new world order should be forged. In many cases, the start has been confusing and even bumbling. Leadership has often challenged both logic and statecraft, but the stubborn determination remains resolute.

From the end of the Cold War until now, both the American people and their leadership failed to appreciate the timing and necessity of constructing a world order that reflected their own moral and political values and the principles which underpin western civilization. As Ambassador Strausz-Hupe described it in 1995, “U.S. statesmanship has failed to make this goal explicit. As a result, American public opinion fails to grasp the ineluctable necessity of it. And, of course, the mythology of the United Nations befogs the reality of a world at the brink of anarchy.”4

Thus, the United States had been momentarily suspended by mythology (or mediocrity), but this was not always the case and, given the probability of the rise of leadership, the vision which created the United States originally has returned after 9/11 to help construct a world order. That is a related meaning of Inaugural Addresses.

The creation of a New World Order which reflects American principles, rather than the common denominators of universalism, lies within the character of the American people and their principles of government and society. In an age of multiculturalism, political correctness, and globalization, it is fair to say that many of these first principles have been submerged within what Strausz-Hupe has called an intellectual and political climate which “befogs” reality.

Drifting but not lost, the American character has the capacity to lead the world in ways far more profound than military, economic, or cultural domination. The notion that Americans have more to give to the world than cars, airplanes, movies, or hamburgers is a recognition of the profound contribution which this society has bestowed upon the moral and political development of civilization. Character lies within the personality of a people and, like individual personality, is a phenomenon given at birth and incorporated within the history and tradition of national life. It can be submerged for long periods but is rarely eliminated.

The military historian, Russell Weigley, has made this point in The American Way of War. Reflecting on American military history as “ideas expressed in action,” Weigley has noted that,

“This book of history, like probably most histories that look back beyond only yesterday, is based on an assumption that what we believe and what we do today is governed at least as much by the habits of mind we formed in the relatively re- mote past as by what we did and thought yesterday. The relatively remote past is apt to constrain our thought and actions more, because we understand it less well than we do our recent past, or at least recall it less clearly, and it has cut deeper grooves of custom in our minds.”5

So, too, should we refer to the remote past, submerged in the collective memory, in order to find the first principles that governed American statecraft from the outset. Within these, if Weigley is correct, we should find the roots of a world order based upon the ideas and traditions which characterized the world’s first and most important political revolution. While the New World idea inherent in American exceptionalism has been momentarily dormant, the notion has always rested just below the surface of U. S. diplomacy as “ideas expressed in action.”

Such an American weltanschauung surfaced in the last century in 1940, when Henry Luce first coined the term “The American Century,” but the conceptual origins for this type of universal political vision is at the root of the American political experiment.

This experiment involved a nationalism as well, but American nationalism was always an idea rather than a people or territory. As defined by the renowned historian of nationalism, Hans Kohn, American nationalism has been woven together through political commitments and principles rather than through social, religious, or geographic components. It is almost identical to classic patriotism. “In its very origin as a nation,” Kohn wrote, the United States embodied a nationalism where “free human decisions” played the predominant role rather than the “natural and subconscious forces” which shaped the harsh nationalist destinies of the more homogenous societies of Europe and Asia.6

Much has been studied about the American tradition (or the several traditions) and the national character as these concepts apply to foreign policy. Indeed, there is an embodiment of experience and belief system that summarizes the American strategic culture and distinguishes American behavior and attitude from friend and enemy alike. As the British strategist Colin Gray has noticed, the American “way” from the beginning has been “first to identify a more perfect international order and then to identify policy intended to give reality to the ideal.”7

This is so, and even necessarily so from the American perspective. The history underlying this American strategic culture, like most histories which look back beyond the moment, is based upon the assumption that what the country believes and how it behaves is governed more by the habits and mindset formed in the remote past than by the expediencies of the moment. This remote past is at least partially subconscious, but it informs and shapes the collective mentality or character more than current events because it has defined the deeper realities and political customs of the population to a point where they become instinctive rather than reflective.

Under the belief that the nation’s earliest vision of itself still has significance, therefore, it is proper to inquire as to the location of the roots of this set of ideas in foreign policy. Indeed, it is equally proper to assert that this vision may even hold the key to a future world order. To do otherwise would be to concede that the forces of modernity have triumphed over the original wisdom of the Founders of the Republic and that ideas, rather than being universal and timeless, can be cast aside by the passions of the moment or by the ideologies of succeeding generations.

To be continued...

Notes

1. Jefferson, Thomas. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. (Cincinnati: H.W. Derby, 1859), p. 157-158.

2. Robert Strausz-Hupe. Democracy and American Foreign Policy. (New Brunswick: Transaction, 1995), p. 178.

3. Ibid. p. 171.

4. Weigley, Russell. The American Way of War:A History of United States Military Strategy and Policy. (Indiana University Press, 1977).

5. Hans,Kohn.American Nationalism:An Interpretative Essay.(New York: The Macmillan Company, 1957)

6. Gray, Colin S. The Geopolitics of Super Power. (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1988), p. 1.

7. Hartz, Louis. The Liberal Tradition in America: An Interpretation of American Politi- cal Thought Since the Revolution. (NewYork: Harvest Books, 1955), p. 58-59.