Purpose in Foreign Policy: United We Stand

“Great minds have purposes, others have wishes.” - Washington Irving

If one were to isolate a single word in all language as the “most important” what would it be? I would choose “purpose” but that, of course, is purely subjective.

The dictionary definition of purpose is “the reason for which something exists or is done, made, used, etc.; an intended or desired result; end, aim, goal" (WordReference.com). The purpose of this essay is to apply the word “purpose” to American foreign policy. Not to “discover” a purpose but to determine if there is one and/or what it might be.

On an even “lower” dimension, every country on earth has a “purpose,” even if it is shared on the most remote level. Survival, prosperity, safety, existence, continuity might define the basics for all 193 UN members. In American history there have been many “purposes,” all of them temporal and expedient: Washington (against entangling alliances), Jefferson (Empire of Liberty), Polk (Manifest Destiny), Teddy Roosevelt (imperialism), Wilson (war for democracy), Coolidge (isolation), Franklin Roosevelt (Four Freedoms), Truman (containment), Reagan (Cold War victory). Since then (1991) the country has decidedly turned “inward,” with slogans as “Assertive Multilateralism” (Clinton), “Nation-Building” (Bush), “Leading From Behind,” (Obama) and “Greatness” (Trump). Many think, including President Biden, that “Climate” is the purpose (i.e. earth, Biology). But with regard to other countries, interests and diplomacy what is America’s ultimate purpose?

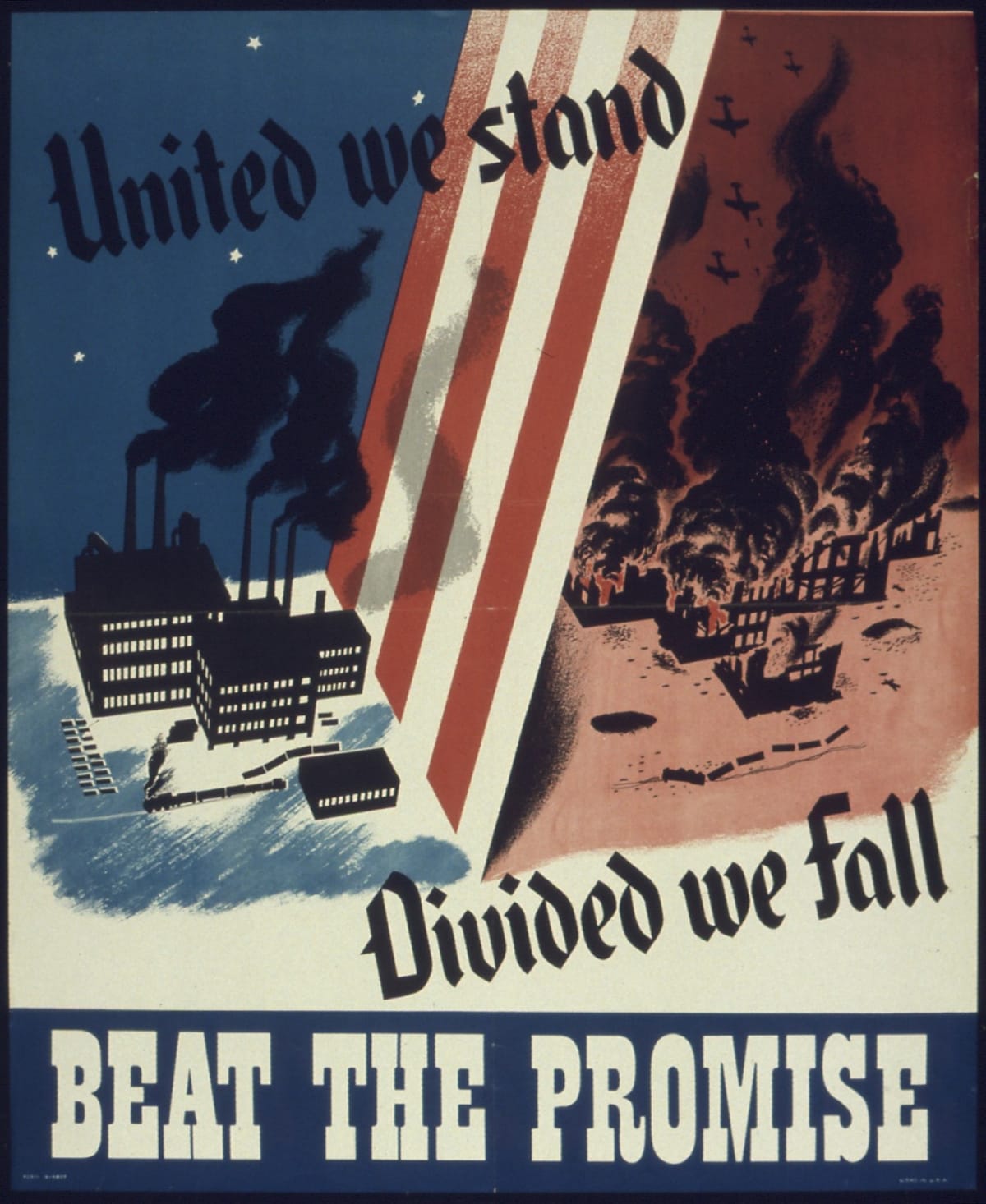

To appreciate this we must begin with the beginning. The title of this essay “United We Stand,” and its corollary, “Divided We Fall,” is perhaps the most famous political slogan in history, going back to The Bible itself. Taken alone, the phrase implies other obvious clichés: that “two can do better than one,” or that “there is no I in team.” The phrase is also known throughout colloquial life, most often to inspire unity among division, for collaboration as opposed to individualism and the notion that union, coalition and alliance is nearly always the key to success. To cite perhaps the most obvious example for this topic: it was no coincidence that the victorious side in the great Civil War called itself “Union,” compared to the loser, "Confederacy” (or “rebel”). Note also that the two great English-speaking sovereignties in the world both begin with the same adjective, “United” (USA, UK). Contradicting this expression is the contemporary American ideological notion that “diversity” is superior to unity in secular affairs, with the attendant notion that the several independent elements of the population should receive priority over the forces for national unity. That this may lead, ultimately, to dissolution and disappearance, apparently, is of little concern to current ideologues.

Although the literal use of the phrase “united” is normally political, the meaning can apply to life itself and goes back as far as Ancient Greece, where Aesop wrote “The Four Oxen and the Lion”:

“Four oxen were grazing in the grass while a single lion watched them but didn’t dare attack. The oxen then began to quarrel and separated. The lion then attacked each one until they were all devoured.”

A similar phrase can be found in the Bible, “And Jesus knew their thoughts, and said unto them, Every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation, and every city or house divided against itself shall not stand” (Matthew, 12:25). In Luke 11:17 we read the same, “But he, knowing their thoughts, said unto them, Every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation, and a house divided against itself falleth.”

Technically, the first public American use of the phrase “United We Stand” came in 1768 when Founding Father John Dickinson used it in his patriotic verse The Liberty Song, which was published in Pennsylvania newspapers. Patrick Henry said the same in 1799, hours before his own death. But the most famous expression of the phrase in its literal and historic sense was in 1858, on the verge of Civil War, when Senate candidate Abe Lincoln predicted that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.” The resultant Civil War, still the most disastrous event in US history, gave power and influence to the slogan itself and has, henceforth, become the standard when defining the limitations of political debate, ideologies and belief systems. If slavery was worth the price of national disunity, Confederate leaders believed, then secession must be the ultimate result. It took the greatest war in American history to prove them wrong. Beneath the central notion in this scenario lie a set of belief systems that, taken together, support and provide “cause” behind the ultimate demand for unity. Unity is necessary for these beliefs to even exist, and this phenomenon is also universal. No political authority, democratic, authoritarian or totalitarian, can succeed in its aims and objectives without a unified populace, be it forced or elected. The Nazis needed Mein Kampf and Hitler, the Communists needed Das Capital and Marx. Christianity needed the Bible and Christ. Islam needed the Koran and Mohammed. In summary, a felt sense of “mission” and desire to shape the political universe underscored the impulse of the original Americans and this became an ultimate raison d’ état for all those who followed them.

Few of those would quarrel with the exclamations of Herman Melville that “God has predestined, mankind expects, great things from our race; and great things we feel in our souls,” or Benjamin Franklin’s assertion that the American cause is “the cause of all mankind … assigned us by Providence.” Historian Edward M. Burns summarized this general belief as follows:

“To a greater extent than most other peoples, Americans have conceived of their nation as ordained in some extraordinary way to accomplish great things in the world. For some of her leaders this mission has been interpreted as ethical and religious. Because of our virtues we have been chosen by God to guide and instruct the rest of the nations in lessons of justice and right.” (Washington Post, Book World, May 5, 2007, p. 10)

The central theme of a democratic “unification” will be shown as originating within America but expressed primarily in foreign policies over time, i.e. how to “democratize” the rest of the world. Fundamental to these policies were beliefs in the inherent goodness and perfectibility of man and a definition of “Freedom” as basic to any past achievements or inventions of mankind collectively. “The magnet and gunpowder … the printing press itself," wrote John Adams, “could not forever extinguish the light of reason in the human mind … man has a right to the exercise of his own reason.” These virtues, furthermore, were universal and not confined to any particular class or nation. Such beliefs gave momentum to the “missionary” (or “crusader”) side of the American character. The Revolution of 1776 united the Founders, and their successors, that this was not just a unique and isolated event but a necessary part of the history of liberty. As John Quincy Adams wrote in 1823, while drafting the Monroe Doctrine, “The influence of our example has unsettled all the ancient governments of Europe. It will overthrow them all without a single exception. I hold this revolution to be as infallible as that the earth will perform a revolution around the sun in a year.” Such an “organic” philosophy of life determined the development of unification as required for the same virtues of political life. Like “concentric circles” the first must give way to the second, the third to the fourth etc. until unification is fully achieved and liberty available to all: first colony, then country, then continent, then hemisphere, then the Atlantic World and, finally, the world itself.

The corollary to the title phrase, “Divided We Fall,” is likewise as relevant now as before. So long as the divisions between the two halves can dominate American history the fact of ultimate and possible fatal dissolution remains at all times a real and distinct possibility. Even today the USA remains a political being (“country”) but rarely a sociological one (“nation”). The rare times of unity occurred due to war and/or economic calamity, which, when overcome, led back again to division.

The divisions inherent among the populace, then as now, have equally prevented, from the Preamble, “a more perfect union” from being formed. The Preamble set the stage for the Constitution and clearly communicates the intentions of the framers and the purpose of the document.

But the Preamble is an introduction to the highest design of the land, but it is not the law. It defines neither government powers nor individual rights. In an existential scheme, unification has been considered essential for the laws and rights that have been defined as the actual purpose of the “United” States.

Conclusion

If unity is the eternal and substantive goal of the American “purpose” in foreign policy then how/where should it be manifested. The next essay will directly address that fundamental question.